The world’s magnificence has been enriched with a new beauty: the beauty of speed’ (Filippo Tommaso Marinetti). The famous aphorism, never more so than on this occasion, has a high semantic value for presenting a car that constituted a milestone in the history of so-called ‘supercars’, luxurious sports cars: the ‘Lamborghini Miura P400.

Linked to a thousand episodes that have created a myth of it that is unscratchable, both by the passage of time and by subsequent advances in technology. The Miura was in some ways anticipated by the ‘TP400’, a sheet-metal ‘chassis’ comprising a transversely displaced engine, suspension and wheels, presented in 1965 at the Turin Motor Show. Nuccio Bertone, the owner of the Turin coachbuilder of the same name, noticed the prototype and, with a phrase that has gone down in history, offered Ferruccio Lamborghini his collaboration: ‘I am the one who can make the shoe fit your foot. Now, beyond the breach metaphor, Bertone knows that he can afford such a statement because he is indeed one of the best coachbuilder designers and because he takes advantage of the absence of collaboration with Lamborghini’s historical rivals Ferrari and Maserati. ‘It will be good publicity, but we won’t sell more than 50,’ is Lamborghini’s famous quip.

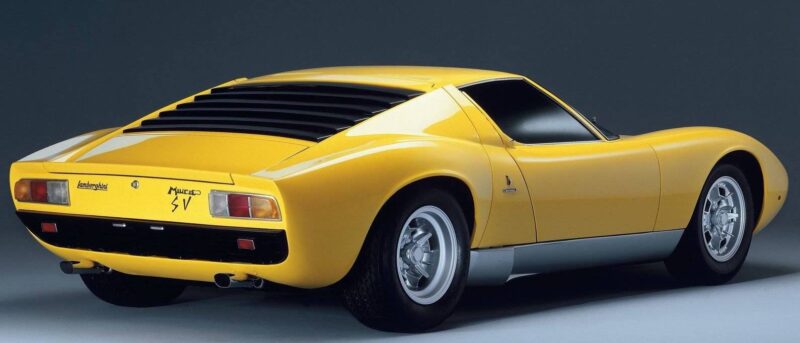

In just four months and under the supervision of Paolo Stanzani, the young designer Marcello Gandini (who had recently become Bertone’s chief designer to replace Giorgetto Giugiaro) produced the profile of the new car, which was to be called the ‘Miura P400’, losing the ‘t’ of the previous version but gaining in lustre and prestige. Gandini himself declares in an interview that the immeasurable advantage of his contribution to the project consisted both in the ‘absolute freedom left to him by Lamborghini’ to realise his ideas and in ‘having so little time at his disposal that he had no second thoughts. The chassis, not even imagined otherwise, is made by Gian Paolo Dallara, perhaps the best historical designer of the important automobile structure. The engine, with a declared output of 350 hp (260 kW) and the work of Giotto Bizzarrini, is the 3.9-litre V12 with four new Weber 40IDL3C three-body carburettors. The novelty, striking for the time, is the central position of the engine, mounted transversally between the cockpit and the rear axle to considerably reduce the footprint, a solution taken up by the racing world.

The Miura P400 was unveiled at the 1966 Geneva Motor Show and was an immediate success, making all other supercars of the time look ‘old’ and ushering in a new era in the ‘sports car’ sector. Incidentally, the same model in the exhibition was exhibited immediately afterwards at Bertone in Grugliasco (TO) and was the protagonist of a curious anecdote. Bob Wallace, a mechanical test engineer, a driver famous for his love of extreme speeds, was commissioned to take that example back from Grugliasco to the parent company in Sant’Agata Bolognese. On this occasion, Marcello Gandini, in a hurry to get back to Lamborghini, asks him for a lift, trusting in his fast driving skills. The journey, however, turns out to be incredibly troublesome due to the hydraulic clutch control that locks as soon as the temperature rises: every 15 kilometres, they will be forced to stop, switch off the car and wait for the temperature to drop. “Had I been on a bicycle, I would have taken much less time!’ (Marcello Gandini).

With the Miura began the series of Lamborghini designations inspired by bullfighting, from the ancient Greek for ‘battle between bulls’, and this racing spirit also characterises its extremely physical and demanding driving style. The driver, lying down almost as if he wanted to increase aerodynamics inside the cockpit, keeps his knees bent to have a more significant muscular travel on the pedals. At the same time, he must have his arms fully extended to hold and direct the ‘Triassic’ steering wheel as if he were waving a hypothetical muleteer in front of the steaming bull. This position is even exasperated when the petrol in the tank at the front of the car decreases, and the car tends to surge as it gets lighter.

Speed (390 km/h maximum in the fastest models), the beauty of which is recalled in the opening by Marinetti’s aphorism, can sometimes become a problem when supported by an inflexible chassis. The physicality of driving is also stressed by the ‘hardness’ of the controls, from the clutch, the accelerator, and the gearstick lever. How then can one fail to notice the mighty engine noise placed a few centimetres behind the driver’s head? This consistency is unthinkable for a modern-day car.

Ferruccio Lamborghini was able to keep his jewel, the Miura, on display in the car park of honour of the Hotel de Paris, much to the envy of Enzo Ferrari and Alfieri Maserati’.

This emphasises how precisely the supposed flaws sometimes become unexpected and unimaginable virtues that move people.

Article edit by Roberto Castellucci