The Divine Artist, painter of the eternal beauty of the Renaissance Madonnas, and the last emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, famous for his extravagance and self-aggrandisement, are the protagonists of the exhibition “Raphael and the Domus Aurea. The invention of the grotesques”, which opened to the public on 23 June and will run until 7 January 2022. Originally planned to coincide with the five hundredth anniversary of the death of Raffaello Sanzio (Urbino, 1483 – Rome, 1520), which fell on 6 April in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic, it was rescheduled for this year at the Colosseum Archaeological Park.

An updated lighting system and a new entrance that starts from the Oppian hill and winds its way along the ruins to lead directly into the Octagonal Room, have helped to re-establish the splendour of Nero’s palace, together with the setting up of sculptures that until now were preserved in the depths of the monument. A memory of the splendour of marble that, in addition to paintings, stuccos and mosaics, adorned the rooms of the imperial palace: all shown under a new light, sustainable lighting of the spaces accessible to visitors in the Domus as a whole, even the buried parts that erased the memory of the site after the damnatio memoriae of Nero and which are still present in some areas.

It is a story that began around 1480, when some painters – Pinturicchio, Filippino Lippi and Luca Signorelli were among the first– descended by torchlight into the caves of the Oppian hill, to admire the pictorial decorations found in ancient Roman settings, from then on known as grotesques. Unbeknownst to them at the time, they were exploring the forgotten ruins of Nero’s immense residence. Raphael was the first Renaissance artist to fully understand the logic of the decorative systems of the Neronian palace and reproduced them organically, working together with students and collaborators, in numerous masterpieces as decoration for rooms especially designed in the style of days gone by.

The growing interest and love for antiquity that characterises the Renaissance are well represented in Raphael’s letter to Leo X that accompanies the collection of drawings of the buildings of imperial Rome, executed on commission from the pope, in which he expresses awareness and regret that the disappearance of classical art is due to neglect, and not only to historical factors such as the barbarian invasions: “[…] how many, I say, Popes have waited to ruin ancient temples, statues, arches and other glorious buildings!”. He therefore advocates restoration and reconstruction works, effectively acquiring the perfection of ancient art as a golden model.

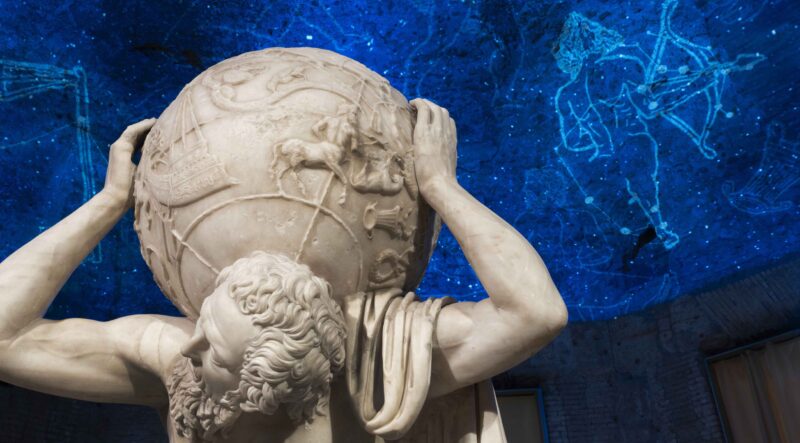

But let’s turn our attention to the exhibition. It all starts in the Octagonal Room, a masterpiece of imperial Roman architecture, and then continues in the five neighbouring rooms. Suetonius, in the “Life of Nero”, recalls that in the Domus Aurea the most memorable banquet hall “was round and revolved all day, continuously, like the earth”. To evoke this coenatio rotunda, a rotating projection of astrological images inspired by the globe of the famous Farnese Atlas was created on the vault, an exceptional loan from the National Archaeological Museum of Naples. These alternate with the projection of falling rose petals which, as Suetonius described, took place during the emperor’s banquets.

Fantastic beasts, harpies, musical instruments, beaded vases and palmettes are among the decorative motifs that ran all the way through the Domus and were later discovered by the artists who found their way into the caves: in the first room, it is the visitor who triggers this story by moving their own body, simulating the flickering flame of the torches used at the time to illuminate underground environments. The second room is dedicated to the study of grotesques and their reinterpretation by Raphael. The spectacular centrepiece of this nucleus is the multimedia reproduction on each wall of the Stufetta del Bibbiena, the incredibly beautiful private bathroom to the cardinal’s apartment built in 1516 to a design by the Urbino-born artist. The Laocoön group of sculptures, found in 1506 in an underground space in the same area as Nero’s palace, is the protagonist of the third room with an audio-story that narrates its memorable discovery. Copies and variations of this sculpture follow one another, morphing against the background of the plaster moulding of the Laocoön, on loan from the museum of Palazzo Albani in Urbino.

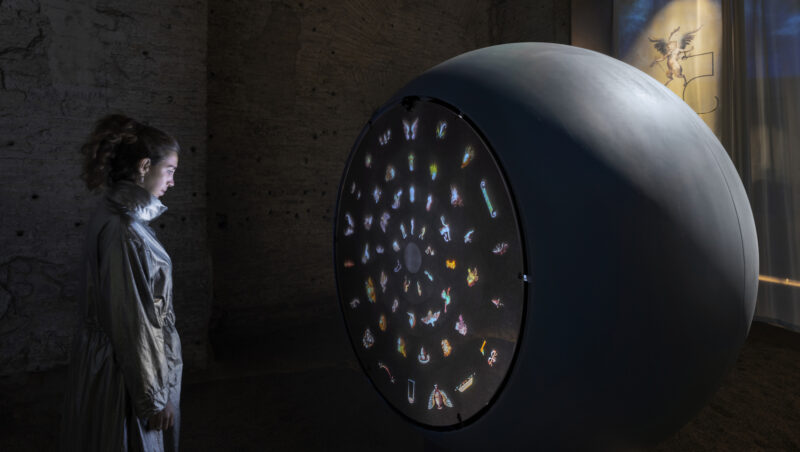

It continues with an interactive handset that allows visitors to travel in Italy and Europe passing through the many places adorned with grotesques between the 16th and 19th centuries: from the Uffizi Galleries to the residence of the Duke of Bavaria Louis X in Landshut, from the Peinador de la Reina, built around 1537 at the behest of Charles V in the Alhambra in Granada, to the Gallery of Francis I at Fontainebleau. The grotesques have also fascinated great artists of the twentieth century, including exponents of Surrealism such as Victor Brauner, Salvador Dalì, Max Ernst, Joan Miró and Yves Tanguy: a hemisphere allows visitors to play around and create digital collages even with their works and closes the exhibition accompanied by a soundtrack that is the result of in-depth historical research on the music of ancient Rome and the melodies of the Renaissance, performed with digital tools of generative music that evoke the sounds of instruments of the past and musical scales of the ancient era.

“Here lies Raphael. Living, great Nature feared he might outvie her works; and dying, fears herself may die” reads the epitaph on his tomb written by Pietro Bembo. He was buried in his beloved Pantheon, like royalty, and his remains lie within a Roman sarcophagus from the 1st century AD. donated for his burial by Pope Gregory XVI.

Raffaello e la Domus Aurea. L’invenzione delle grottesche

23 June 2021 – 7 January 2022

Rome, Domus Aurea

Set Up and Interaction Design by Dotdotdot

Photo by Andrea Martiradonna ©

All rights reserved Dotdotdot/Erco Illuminazione

Article Edit by Claudia Chiari